Melika Bass is a moving image artist who makes abstracted atmospheric film worlds, as well as immersive site-specific installations, often captured on 16mm celluloid, and featuring intricate, visceral soundscapes. Her films and installations include:Vardeldur (Sigur Ros’ Valtari Mystery Film Experiment); Waking Things; Shoals; Songs from the Shed; Bulb in the Head; Story Ever Told; Asleep in the Deep; Holguin; The Latest Sun is Sinking Fast; Slider; Nanty; Nocturama.

Her works were exhibited at Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (solo exhibition); Film Society of Lincoln Center, New York; Kino der Kunst, Munich; Torino Film Festival, Italy; Anthology Film Archives, New York; Los Angeles Film Forum; Indie Lisboa, Portugal, among many others. Melika has also received 2 Media Arts Fellowships, Illinois Arts Council; Kodak/Filmcraft Imaging Award, Ann Arbor Film Festival; Experimental Film Prize, Athens International Film Festival; Pick-Laudati Resident Artist, Alice Kaplan Institute for the Humanities, Northwestern University.

Melika joins Artadia for a brief discussion about her work.

A: You received the Chicago Artadia Award in 2008. Can you talk a little bit about what you were working on at that time?

MB: My cohort of Chicago Awardees that year was amazing: Kelly Kaczynski, Theaster Gates, Jim Duignan, Kim Petrowski, Juan Angel Chavez. Fierce group of artist-humans there.

When I met with the Jury in 2008, I had just shot my prairie grotesque film, called Shoals. To make the thing, 12 of us camped out for weekends in August at my friend’s farmette in Wisconsin, shooting on 16mm film, hanging with lots of bugs in the noontime sun, the air reeking of manure from over-crowded dairy barns nearby. It was a fun and visceral experience. The film is creepy and slow-burning and dryly funny, like a lot of my stuff. Shoals centers on a small, fictional rural community run by a half-baked, self-made cult leader who purports to help young women by enlisting them in absurd physical labor and by harvesting liquids from the bodies. I had made a film before, Songs from the Shed, that also featured an enigmatic ‘chosen family,’ but Shoals playfully grabbed at a bunch more stuff — horror, American transcendentalist poetry, and pastoral landscape painting. It turned into an atmospheric fable with musical interludes that skewers patriarchal utopian fantasy.

The surprise of the Artadia award was awesome. It helped me finish Shoals, which premiered as a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. All the tactile and highly formal parts of the work got enlivened in the museum — the creepy-crawly film grain, clammy and sweaty color temperatures, blasted out white sunlight, and sonic detail that rendered surface details and texture.

The Award was bolstering, and landed at a key moment – my practice evolved from standard cinema showings into immersive museum presentations of my moving image work. Now, ten years later, I’m a hybrid installation artist and film artist, and I relish playing with the differences between the two. The recognition and support by Artadia opened several brain-doors. I discovered the quiet social politics of witnessing art in a public space, something that can happen to visitors while navigating multi-channel set ups – large, portrait-landscape projections with immersive soundscapes.

A: What are the influences behind the lush, gothic landscapes in your films? Can you speak about the importance of place or location in your work?

MB: The easy answer is growing up in the American south. Sounds cliché, but there’s something to it. Southern Gothic is an actual thing, and I’m sure I got my sense of ‘vegetable darkness’ from childhood in places and cultures steeped in dark (semi-hidden) histories; in the verdant landscapes, and really just all of the expressive, lyrical weirdness that abounds in both people and place in the South. For all the flash of urban American culture, our violent colonial history is of course not remotely resolved, and it is differently visible in smaller cities and towns, often quietly ever-present. In a way, the tense, dark pull of the Gothic keeps the troubling feelings bubbling on-alert, a reminder that history and the present live together, intertwining.

Specific settings in my work are sites for fictional histories that have real-world resonances. These places hold traces of narrative on their surfaces. The details of clothing, objects, and decor can imply so many elements of culture and identity (objects have an emotional life too). My Prairie Gothic films/installations SONGS FROM THE SHED, SHOALS, and WAKING THINGS all have a heightened materiality of place. My Sigur Ros video VARDELDUR takes it further, where the setting is a site of implied trauma, and the fractured figure you find there contains an embattled interior that it’s trying to work out.

This is also related to my adventure in portraiture, which takes a fresh, new turn in my current project THE LATEST SUN IS SINKING FAST, where situations are uncanny, yet sneakily mundane, in a contemporary setting. This new project’s been building in intimacy, over years, and it has some nervy surprises inside its familiar, yet speculative fiction.

A: Unlike most of your previous work, your recent project The Last Sun is Sinking Fast is a feature-length production. Can you talk a little about this transition?

MB: I wanted to make something expansive and epic, that has the weight of real time and real relationships moving through it, but I didn’t just want to simply make a feature film.

I get commissions, grants, a bit of funding here and there, and have summers off due to full-time teaching, so I knew I’d need to construct it gradually over time.

This accumulation of material and parts strategy also allows us to embrace the budgetary and schedule realities. We are now 7 years into making The Latest Sun is Sinking Fast, and have a on-going pattern of shooting, editing and generative rehearsals. People age in real time, so every few years, I check back in with the 3 performers (Bryan Saner, Sarah Stambaugh, and Matthew Goulish) for generative rehearsals. What we make out of those is a combo of prompts from the last round of editing and events in the 3 performers’ lives and family histories. From these creative constraints we’ve built something quite delicate and unnerving, it’s lyrical and funny, and about being alone together.

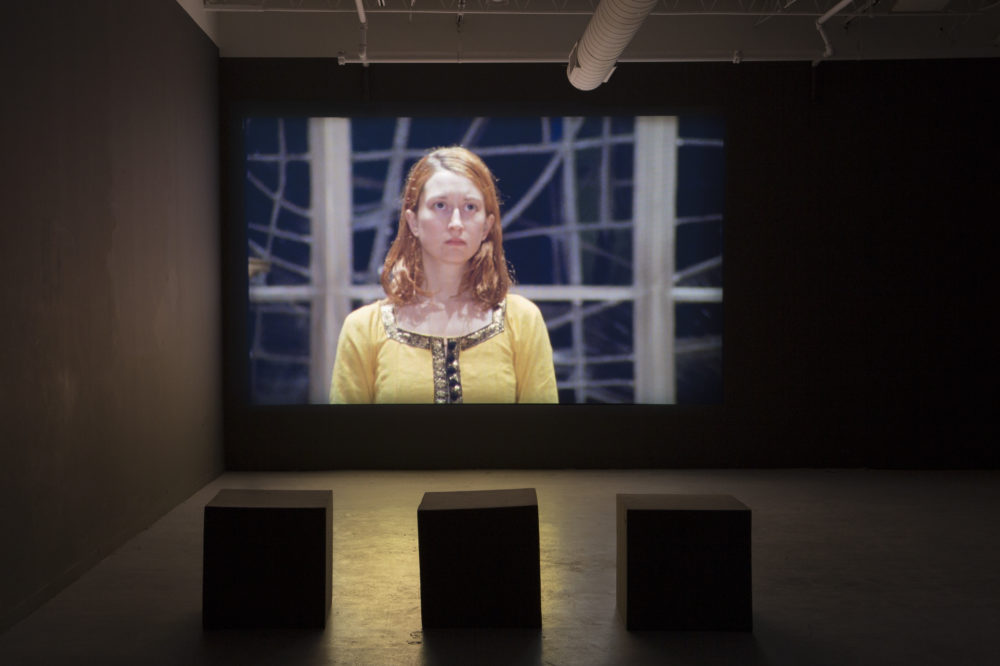

The nuts and bolts of making Latest Sun are dynamic too, as it’s made to work in different modes — to be flexible to show in both art spaces and in cinemas. Each new section we make becomes new material that gets shaped into the next show site-specifically. Each of these iterations is stand-alone; together they accumulate intentionally into a constellation of parts. You don’t need to see everything, as each one is edited and designed experientially for the space its shown in. So far I’ve shown it as a single-channel installation, a duo-channel installation, a split-screen short film, and a 4-channel installation, at venues like the New Museum New York, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and the Hyde Park Art Center.

Right now I’m working on 2 new sections – a linear long-film; as well as a new, multi-channel installation that I hope to mount in a large space or a few spaces in a building. Right now, after 7 years of shooting and editing, there is more material than ever to work with, so the sense of time passing is palpable – just like in real life, we return to these characters after a few years, and unexpected things in their life and with each other, have changed, and our assumptions about who they are are forced to shift.

A: How do you think your work has changed since 2008 and where do you see it going from here?

MB: One continuing thread is I think I’ve always been thinking about human connection, isolation, and what humanism can be now (or if the delusion of its ideal is now done and something new can take its place). Ten years ago, I was making moving image work that was historical fiction or fantasy, with no talking, and now the genre play has moved into abstracted and slow-burning melodrama with Creature Companion, and an epic-of-the-ordinary, with The Latest Sun is Sinking Fast, that brings in another kind of performance -cascades of language in singing and monologuing.

Since I got the award, I’ve delved into some unique qualities offered through installation – viewers’ psychology of navigating art spaces, and viewer agency – the pathways of random access points into the gallery, and the voyeurism of people watching people watch media. These art architectures and bodily performances now inform how I put together my video-sound material and design an installation.

This social context also means I think about audience — how my work connects or does not connect to folks. I made something commercial in 2012, a commissioned Sigur Ros music video, and that was eye-opening. I put an experimental video inside a mainstream platform (you tube) and I loved seeing people fight in the comments about whether it’s ‘boring arty tripe’ or why it had an ineffable power that pulled people back to watch it over and over. That film opened some people up, with its darkness and rawness and ambiguity too. In a similar way, my shows in Museums and Art Spaces give me similar feelings of engagement — sneaking something experimental into a public setting, with just a smidgen of narrative or character to hook people, and then confounding and haunting them, planting the seeds of possibility.

I’ve also started looking at my work as being about whiteness – power, delusion, awkwardness, idealism, and anxiety. My southern, multi-racial family, who I am close to, is educated, liberal, and religious. There are lots of ministers. My work foregrounds absurd gestures and rituals and I think this comes from a family culture. I make these mysterious cinematic-snow-globes, and inside there, you’re looking at meaning-making and power structures within an isolated community, like it’s a fictional anthropology inside a single house, where people are warming up for a religious service. I have a dream project that I want to make that expands this, on the scale of an entire town…

A: Can you talk a little about the intersections of film and installation in your work?

MB: One interesting similarity – my installations and cinema films both have cyclical shapes and embrace the “…” between fragments. As a media consumer, I like being an ‘active viewer’ – working to piece things together- and I expect to do work when looking at media in an art context. There’s something about media-res – dropping a viewer into something in-progress – that feels life-like and brutal to me, and I often use it structurally. When you start a film work in the middle of something ongoing, people have to scramble to figure out the basics of who-what-why-where-how, and I like to open up the possibilities for viewers, a space for contemplation and questions, and then keep playing with their assumptions.

I also love making work site-specifically, to respond to the particulars of architecture, viewer pathways, scale, and attention. Everything’s a site – the cinema with its theatrical fixed seating and idolatrous big screen, the control-inside-chaos dynamic of public spaces with their sound bleed and hubbub; and museum galleries and art space layouts guide me in thinking about sequencing and simultaneity. The contemporary life of media multi-tasking is for-real, and I re-work this behavior inside my media-based art experiences.

A: Are there any artists or exhibitions that have resonated with you lately or have been of particular interest?

MB: There are always many, but a few folks swimming around in my 2 recent projects, Creature Companion and Latest Sun — Swedish filmmaker Roy Andersson, US graphic novelist Chris Ware, Argentinian filmmaker Lucrecia Martel, UK filmmaker Peter Watkins’s Edvard Munch, Canadian painter Peter Doig, Italian novelist Elena Ferrante, US poet Alice Notley, and US Anthropologist-filmmaker Chick Strand.

To see more of Melika’s work, visit her website and Artadia’s Artist Registry.

Melika’s biography and all images courtesy of the artist.

Images:

Melika Bass on the set of Vardeldur / Photo by Jordan Schulman.

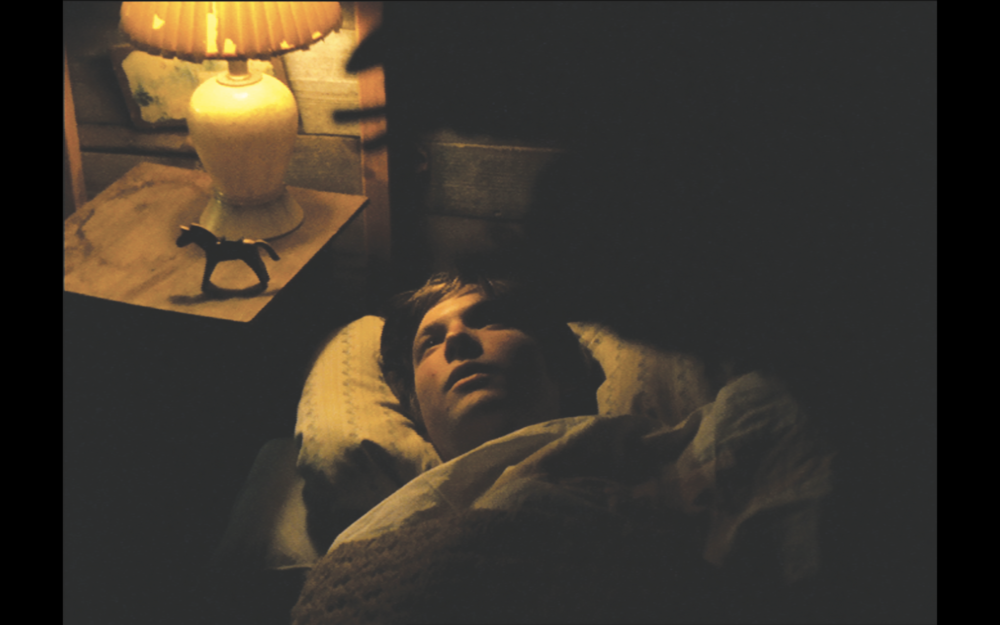

Film still / Creature Companion / 2018 / Super 16mm film / 30 minutes

Film still / The Latest Sun is Sinking Fast / 2013-present / Super 16mm film

The Latest Sun is Sinking Fast / 4-channel installation / 2015 / Hyde Park Art Center / Photo by Clare Britt

Film still / Shoals / 2011 / 16mm film / 52 minutes

Installation View / Shoals / 2011 / Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago / Photo by Jordan Schulman

Film still / Songs from the Shed / 2008 / 16mm film / 23 minutes

Film still / Varðeldur / 2012 / Super16mm film / 6 minutes