Dianna Frid was born in Mexico City. When she was a teenager, Frid immigrated to Vancouver, Canada. Based in Chicago since 2000, Frid has exhibited her work in the USA, Mexico, Canada, and abroad. Her work is in public collections at the Cleveland Clinic, The Art Institute of Chicago, the DePaul Art Museum, and others. A database of her artist’s books is in the collection of the Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Recent exhibits include “Time is Textile” (solo) at the Alan Koppel Gallery in Chicago, and the group exhibit “Headlines” at the Winnipeg Art Gallery (Nov 2023 to May 2023) where twenty pieces of her “Words from Obituaries” are featured. Dianna Frid recently completed artist residencies at the Albers Foundation in Bethany, Connecticut and Joya in Andalusia, Spain. In addition to Artadia, Frid has received grants and fellowships from the Canada Council for the Arts, the Fundación Alfredo Harp Helú Oaxaca, 3Arts, the Illinois Arts Council, the UIC Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs among others. Frid is Professor in the Art Department at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

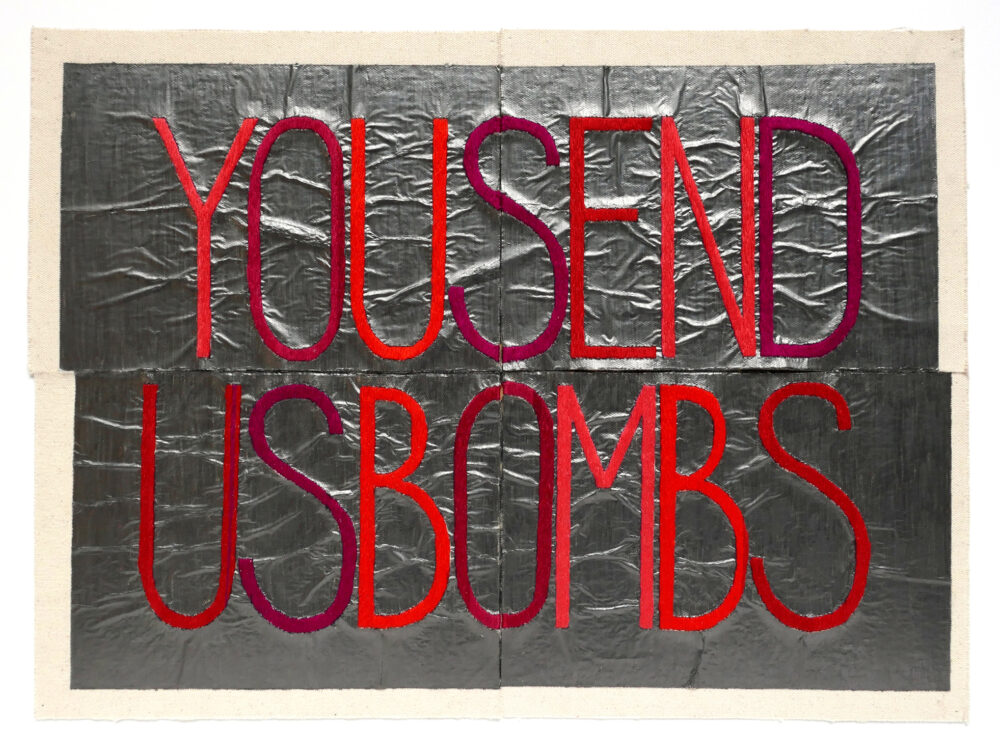

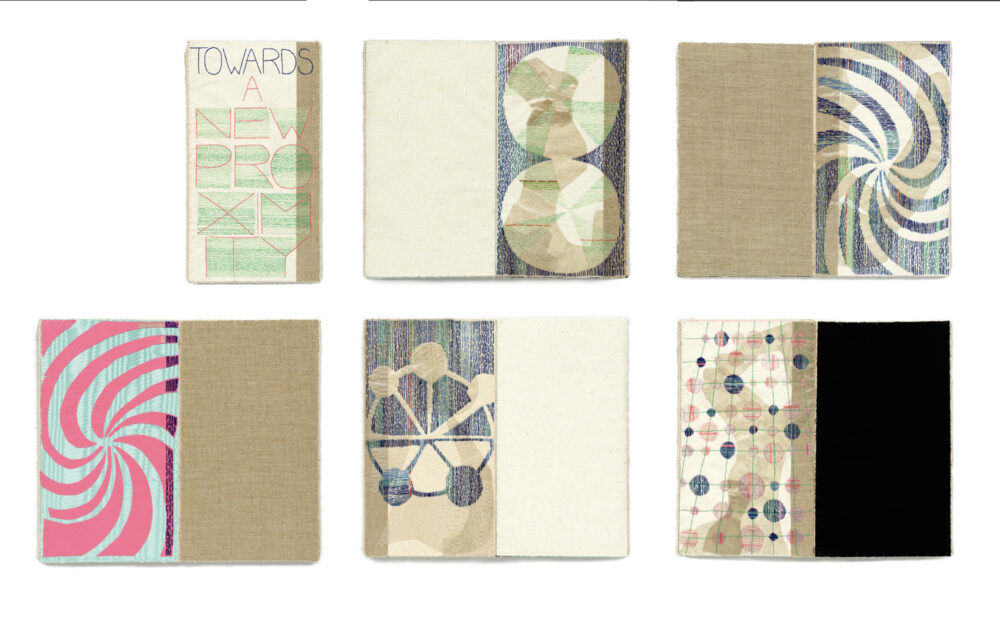

“I typically work at the intersection of material texts and textiles. My artist’s books and mixed-media works make visible the tactile manifestations of language. In my process, embroidery is a prominent vehicle for exploring the relationships between writing and drawing, and the intersections of transcription, translation, and legibility.

In his formidable yet brief book, How Are Verses Made? (1926), poet Mayakovsky refers to “the material of the rhymes” as “stronger than the other lines.” What is this material of rhymes and rhythms that Mayakovsky alludes to? The recognition of meaningful, nonverbal components of language resonates with my understanding of words as part of a larger puzzle. While my practice intersects with and borrows from written language, it also wrestles with language and its limits across the less linguistic aspects of art.

Etymological siblings, the words “text” and “textile” come from Texere—Latin for “to weave.” In her book On Weaving (1965), Anni Albers talks about Inca textiles from ancient Peru as a form of writing. Albers was surely not the first to identify and theorize about this connection, yet her expansive book brings into focus how cloth in art, as much as elsewhere, continues to function as a text—a code. Albers is a model in her refusal to reduce art and craft to neatly delineated categories. In understanding them as interrelated disciplines, I engage with their dissimilarities and correspondences in a non-hierarchical way. This helps me adopt material and conceptual practices openly and experimentally. Through this stance, I can emphasize the YES/AND emergence of the sensual alongside the analytical.

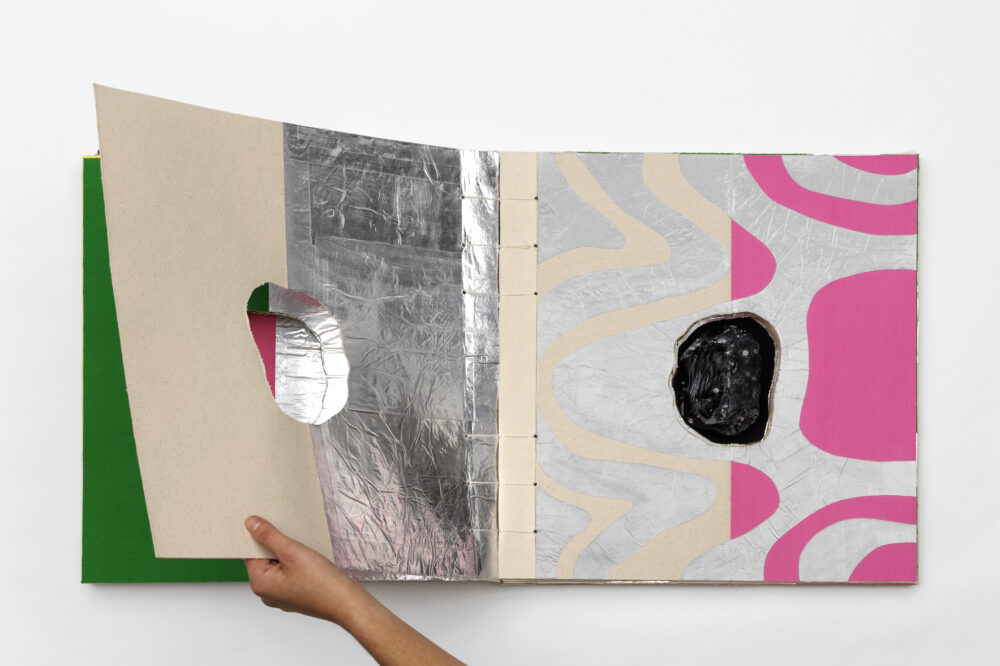

Currently, I am embarking on a new project for which I will be making new work, mainly photographs. These stem from looking at books with wormholes, literally. My study and interpretation of books with holes began when I first encountered the collection at the Burgoa Library in Oaxaca, Mexico. Although I was born in Mexico City and immigrated to Vancouver as a teenager, I have lived in Oaxaca periodically, starting in the early 90s, and have continued to nourish roots and professional connections there. In 2014, I first noticed that many books in the Burgoa Library were riddled with different types of wormholes carved by diverse species of insects. These wormholes are what make this specific collection astonishing—one third of the entire holdings is riddled with signs from ancient larval incursions. While these books have been “cleaned,” they cannot be restored to what we would refer to as “intact.” As a result, their former function as nests has become an integral part of their history and our interpretation of that history: once a dwelling now a void.

Interestingly, in retrospect, I notice that before visiting the Burgoa, I began to make artist’s books with holes. Early examples include “Floyd Collins, Cave Explorer” from 1998 and “Just Wait and See,” from 1996. I joined ranks with other lovers of books, the bookworms of the world, a long time ago.”