A: Can you tell us about your work “Marie”?

My recent show Marie was based on a road trip I took with friends to New Orleans, Louisiana during a summer in the early 90’s. Marie Laveau was a black Louisiana Creole vodou priestess from the late 1800’s who granted wishes by performing special rituals using gris-gris. She would combine both vodou and Catholicism. Legend has it that she initially worked as a hairdresser and was able to gather intel from her clients, which she used to shift and affect politics during that time.

My friend Brendan brought us to St. Louis Cemetery No.1 to shoot a Super 8 horror movie and when I saw Marie Laveau’s tomb, I was struck by how incredible the various markings on the monument were but also how communal and how powerful her grave was by the loading of wishes and dreams on a destination. I was in awe of the force of what I saw. Lined all around the tomb are gifts, knick knacks, pennies, coins, flowers, beer cans, a gathering of all this material from different people.

A lot of my work is about my own memory, and what I was going through and how different the perspective looks from where I am now. I wanted to create this tomb from my memory in 1993. The reason why I surrounded Marie’s tomb with all these pieces from my past is because I have all these boxes of things I’ve collected over the years. They carry whatever memory was embedded during that time when I collected it. I finally found a place to put them – around this tomb. This tomb is not only a place for people to come and make a wish at, a collective space for hope, but it’s also a conglomerate of my life over the last 30 years, and all the emotional intelligence I’ve gained throughout that time. When I went down to the tomb originally, I was an art student. I was confused. I didn’t know what I was doing – I truly did not have much hope. To find a space like that in Louisiana was extremely special and I wanted to somehow carry that into the present.

Supposedly now you can’t visit the tomb without a tour, because 10 years ago it was vandalized by someone who painted her tomb with pink latex paint. When they were trying to restore it, it pulled off a bunch of the plaster and original tomb. I`m not sure if you can mark it up anymore. That made me very sad and that made me think of many memories, where you realize later on that life is different now, that we’re never going to go back to that point when it looked like that and we could feel like that and we could visit like that. I really wanted to capture that moment in time as well as bring that essence and joy and hope to the gallery space. That was the decision to let people mark it up themselves.

A: What’re you working on now?

JJL: I’m going to Korea for the first time since 1988. I applied for this fellowship at Tufts university and I was awarded travel money to go to Korea. I teach ceramics but I know so little about my own culture – being Americanized and whitewashed. And as I live in America, I pay attention to American ceramics foremost. I really wanted to become more educated and aware of Korean ceramics because it goes back so many centuries. And, in turn, learn more about my heritage. I’m planning to visit with ceramic artists and hopefully that will be the beginning of many trips.

Installation View, Marie, Martos Gallery, 2022

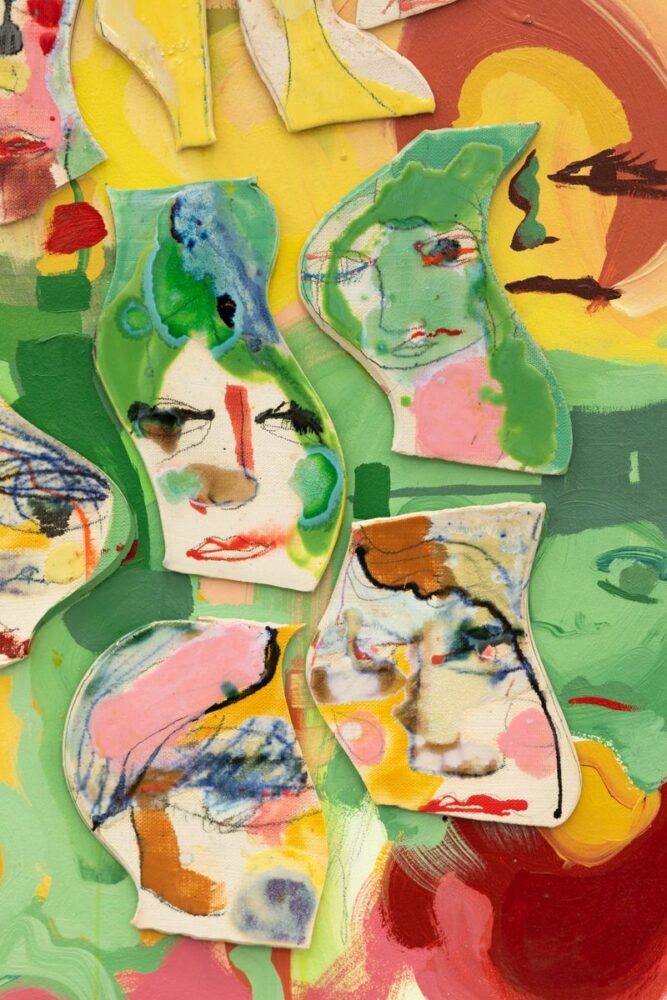

Detail from the exhibition, Marie, 2022

Installation View, Marie, Martos Gallery, 2022

Jieun Lee and her mother when they first moved to NYC from Seoul, Korea, 1976