Mequitta Ahuja is a contemporary American feminist painter who currently lives in Baltimore, Maryland. She creates works of self-portraiture focusing on themes of figurative painting and the artist as picture-maker. Her work has been exhibited at MCA Chicago, The Studio Museum in Harlem (New York), the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery (Washington, DC), among other notable international institutions and galleries. The 2008 Houston Artadia Awardee joined us in conversation.

What were you working on when you received the Artadia Award in 2008? How has your practice evolved since then?

Going back to my adolescence, my story is that I have a relatively unique cultural heritage—I am African-American on my mother’s side and South Asian Indian on my father’s side. In the United States the conversation about race is almost always black and white. If somebody is mixed-race, we assume they’re mixed black and white, not two non-white ethnic groups. Often, I felt like an outsider, and for a long time, creating a visual unity of my cultural heritage was the subject of my work, but as I aged, those concerns receded. At some point, it no longer felt important whether or not I fit other people’s expectations. As those concerns faded, I needed to reinvent my work, and to do that, I needed to expand the terms of the self-portrait. The genre of self-portraiture, especially when it is an artist of color or a woman, is circumscribed by identity and its politics. It became important to me to move self-portraiture, as a genre, away from identity and toward a discourse on representation. That transition is about authority. Because we as women, and we, as people of color, are not only experts on ourselves and on our social condition. I am also an expert on art. My paintings tell you what you need to know about paint – its form, its conventions and its history. As women, as people of color, we can have that authority. I picture it.

What was the impact of the Artadia Award for you? What did you do with the funds? How did it affect your career trajectory?

The impact of these kinds of awards, the Artadia Award or the Guggenheim Fellowship, which I was awarded this year, is three-fold – status, money, validation. As artists, we figure out how to work when any or all of these is in short supply. If we’re lucky, we get occasional infusions of one or another, enough to keep us afloat. For me, the most profound impact of any of these kinds of prizes (when you get them and when you don’t) is always existential and psychological – they contribute to the shape of the story we tell ourselves, about our efforts, our lives, our purpose and those stories are either fuel or weights. Often, it fulfills a need we each have to construct our personal narratives of success and overcoming challenges. The stories we tell ourselves have both psychological and practical outcomes. The confidence they impart makes us better at what we do. It also challenges us to live up to them. Once we receive recognition, we have to prove we deserve it.

Your work repositions portraiture and ideas of representation by layering information, histories, narratives, and material. What are you hoping people will get from your work?

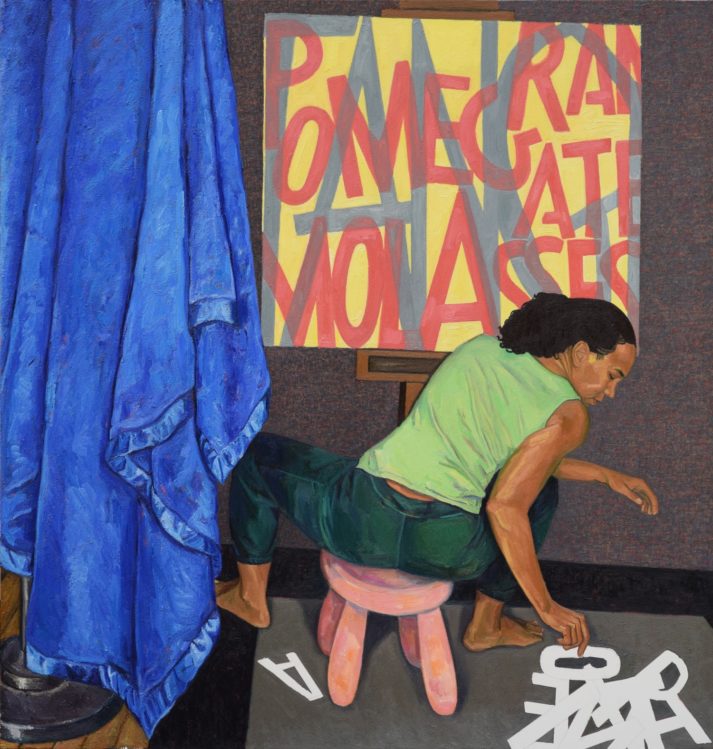

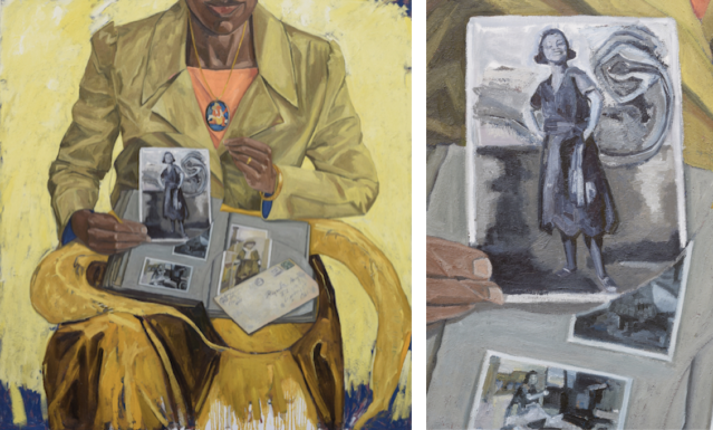

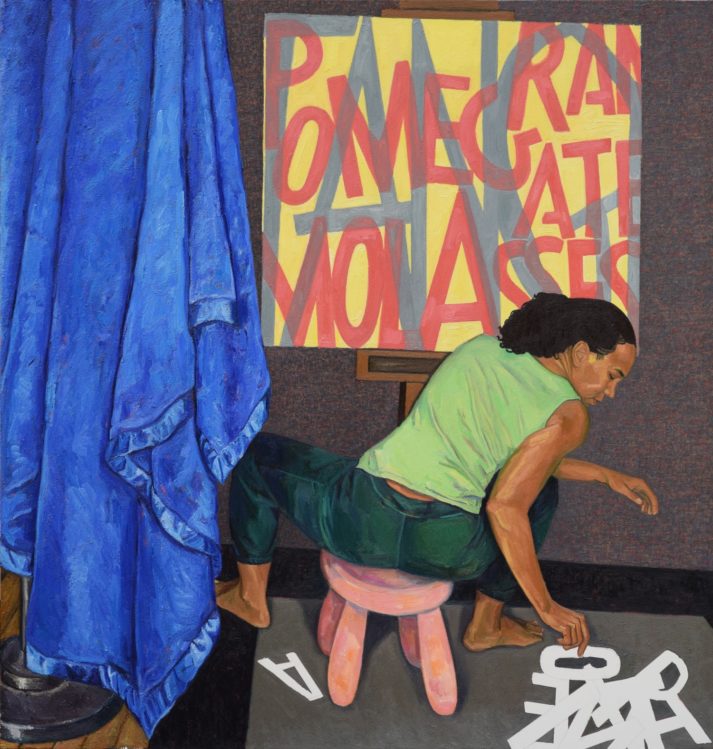

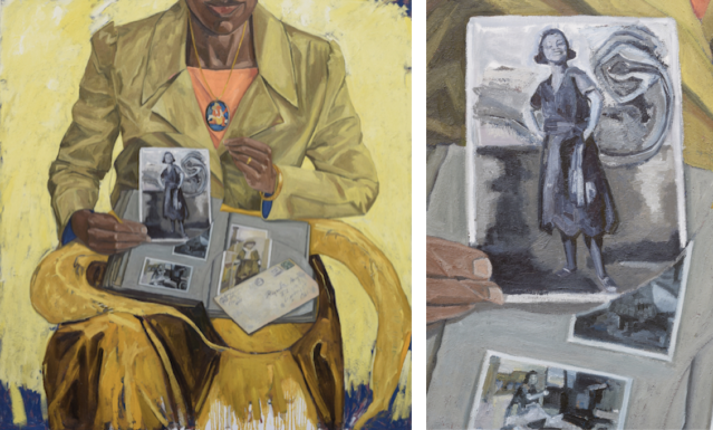

In my works, I position a woman of color at the center of a discourse on representation. I established this objective from my study of art history. It is my assertion that the entire figurative painting tradition can be summed up this way: the figurative tradition is the unseen made visible through a meaningful fiction. Unseen because it happened in the past or away from public view or in the mind of the artist or the sitter. And meaningful fictions include all the mechanics of illusionism such as one-point perspective, or a single source of light, as well as the conventions of painting established and reinforced over the history of painting – ideas like, painting as a stage set established by a pulled back curtain, or using architecture to frame a narrative, or depicting a piece of paper as a trompe l’oeil or “trick of the eye.” I consciously make use of painting conventions to position my work in dialogue with the figurative painting tradition. Often, I include elements in the work that reveal its character as a construction self-consciously staged for a viewer.

What’s next for you?

In my new work I’m addressing domesticity, the body and painting – painting as an act and painting as an object. The work I exhibited in 2017 at the Walters Art Museum was the start of my imagery depicting paintings within paintings. I’m continuing that theme because it allows me to explore the full range of my medium – its full formal and pictorial history. By creating a contrast between the painting’s overall figurative style and the style of the internal painting – the painting within the painting, which ranges from naturalism to folk art to text, I’m able to work expansively across pictorial idioms. Working this way forces me to expand my skills and my references. In my most recently completed painting, “Seated Scribe,” I was influenced by the artist Corita Kent. The process of working on this painting opened up areas of art and art history that I’d barely visited. Before working on the canvas, I first had to wrap my mind around a graphic design problem – how to make something legible that also worked as an abstract pattern. This is not a problem I’d tackled before in painting, so I spent a lot time drawing letters, cutting them out and arranging them on paper then trying to approximate a printmaker’s graphic flatness in colored-pencil drawings before moving into my final painterly approach to the text.

For me, painting, it’s practice, it’s mechanics and its history, is a lens through which I view everything. My daily concerns are formal – questions of mark and surface, structure and space, color and shape. My body of work documents my development as a maker and as a thinker. I want my viewers to see what I see and to see how I visually problem solve, which is a way of thinking. I want the viewer to see me in my process of thinking and painting, painting and thinking.