Nigel Poor is a San Francisco-based artist and teacher. A 2002 San Francisco Artadia Awardee, Nigel “explores the troubling question of how to document life and what is worthy of preservation.” In recent years, she has shifted from a solo studio practice to working collaboratively from inside San Quentin Prison, “working with a group of mostly lifers on photographic projects and producing radio stories about life inside.” Her work has been shown at many institutions including, The San Jose Museum of Art, Institute of Contemporary Art, San Jose, SF Camerawork, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. and the Haines Gallery in San Francisco. Her work can be found in many collections including the SFMOMA, the M.H. deYoung Museum, San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art and Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. She recieved the San Franisco Artadia Award in 2002.

Nigel joins Artadia in a brief discussion on her work and Ear Hustle, a podcast she co-produces out of the San Quentin State Prision in collaboration with artist, Earlonne Woods, currently incarcerated at the Prison, and fellow inmate Antwan Williams.

In a lot of your work, you are exploring how we document life, which events or histories hold value that is worth remembrance, and methods of thinking about representation and preservation. Could you describe what brought you to these ideas?

From a very young age I was a collector, someone who enjoyed picking things up from the ground and finding value in what was there. I think I was in second grade when I started saving shoe boxes which I carefully labeled and stacked in my closet in order to keep my various collections organized: stones, leaves, popsicle sticks, lost buttons etc. I was a shy kid and I think I just found it easier to engage with my own thoughts and build an imaginary world where objects and found items held clues to larger things that were happening around me but that I couldn’t really participate in. The impulse in me to understand the world by collecting, cataloguing and archiving just grew and I found ways to incorporate that in to my art and life.

In graduate school, I worked at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology in the entomology department. Part of my job was to pin insects and create small organized collections of the insects brought back from research trips. Working there gave me access to all the back rooms of the museum where I could freely roam around and open any drawer I wanted. It was a collector’s dream and reinforced my belief that collecting, cataloging and archiving was indeed a valid way of problem solving and understanding the world.

There is a tradition of photographers working as archivists, collecting large samples of images in hopes of revealing something quintessential about being human. One example is August Sander, whose project, Citizens of the 20th Century, attempted to create a complete photographic mapping of “types” of Germans in order to explain how society is organized.

My work uses collecting and archiving as a strategy to understand who and what we are. Sander inspires me but I also take delight in people like the 19th century scientist Francis Galton who was obsessed with counting and undertook bizarre projects like The Beauty Map where he walked the streets of Britain recording the appearance of each women he passed using a concealed pocket device of his own invention called the pricker. He then recorded the results to literally produce a map of Britain based in his personal ideal of beauty.

My work explores how people leave behind evidence of existence. I am interested in portraiture and explore it through unconventional means. I have used fingerprints and hands, objects people throw out, human hair, dryer lint and dead insects as indexical markers of human experience. I am exploring how to document life and what is worthy of preservation.

In 2011 my interest in exploring the marks people make led me to San Quentin Prison where I became a volunteer professor for the Prison University Project, which is a program at San Quentin State Prison where men can earn an AA degree. For three semesters, I taught history of photography classes and that experience changed my once solo studio practice. I now spend most of my time inside the prison working with a group of incarcerated men on photographic and audio projects.

When did you arrive to the Bay Area? Why? How has the Bay Area influenced your practice?

I was living in Boston at the time and a little bit at loose ends after finishing graduate school at Massachusetts College of Art. My sister was living in San Francisco and I came out to visit her. I fell in love with San Francisco, went back to Boston tied up some things, packed up my possessions and drove across country. I didn’t really know anyone here but my sister, I didn’t have a job and I didn’t have a real plan except that I wanted to be an artist. The Bay Area wasn’t crazy expensive then, it was 1992. I got a series of unimpressive jobs to pay the bills and I kept making art. I thought San Francisco was a quiet and kind place and it suited my temperament. But those aren’t the words I would use to describe it now.

I don’t know if the Bay Area has influenced my practice but it was the place I matured as an artist. It was so different from where I grew up in New England and at the time it felt like a freer place where people came to be themselves. I spent a lot of time walking around the city, years actually, just walking and looking and it seemed ok to let things unfold.

I do remember during a particular period I was feeling pretty down and I decided to just walk until I found something that would interrupt my sadness. The first days I walked until I ended up at a huge rundown church- I wanted to go in and explore but none of the doors were open. That surprised me because I thought churches never locked their doors- not sure why I thought that except in Vermont where I had gone to college churches were always open at night and you could go in and just sit. The next day I walked again until I ended up at a place called The Friends of Photography which was a non-profit photography center. I asked if they took on interns and they did. From there I met a lot of other photographers, got involved with things and started to become part of the photographic community here. Walking, thinking and looking for the unexpected connections has always been what moves me forward.

Can you tell us about Ear Hustle and your work at the San Quentin prison?

While teaching for the Prison University Project I was so inspired by the conversations we had in class that I became determined to find a way to work on a collaborative project with the men inside. In 2012, I started a radio project with some of the men I had met while teaching. I worked on that for several years but eventually found myself wanting to do something different, something more artistic and less journalistic. During this time, I met Earlonne Woods who is serving 31 years-to-life for attempted second degree robbery. We started talking about the possibility of what we could do and together we hatched the idea for a podcast. We are now the co-hosts and co-producers of Ear Hustle.

In 2016, Earlonne and I submitted an application to a contest that the podcast network Radiotopia was putting on. Out of over 1500 applications Ear Hustle won and that started our professional relationship with Radiotopia which now helps us produce the show and gets it out into the world. Our 3rd season is launching September 12th 2018 and to date the podcast has been downloaded over 13 million times which is pretty amazing for a project coming out of prison, put together by people who have never done anything like this before.

The podcast is a unique partnership of incarcerated men at San Quentin State Prison and myself working together as colleagues to produce stories about life behind the walls. Because we are based inside a prison we have unprecedented entree to a world that most citizens, including journalists, have little or no access to. Our mission is to tell compelling stories that are difficult, honest, funny, poignant and real while revealing a more nuanced view of the people serving time in American prisons. Though the stories concentrate on life inside they ultimately address the larger question about what makes a life and what is worthy of being told.

All the work I do at San Quentin, including Ear Hustle, is about developing committed and professional relationships with the men inside and producing work that challenges stereotypes and gives voice to a population that many prefer to silence.

What challenges have you faced while working on this project?

There are incredible challenges to doing this project: prison is a very unpredictable place- there can be lockdowns that occur and in such a case the men are confined to their housing units so we are not able to work. These can last for days or weeks. Everything inside prison takes time, there are all sorts of protocols that need to be followed. The administration’s first objective is to keep the prison safe, so our needs and deadlines are not a priority. We need to work within a complex framework. If you cannot be patient, persistent and polite you will not make it far as an outsider trying to work within the prison system.

Once I leave the prison I have very little contact with Earlonne, it is difficult to talk on the phone and there is NO email or internet- all our work must be done face to face. Also, once I am inside I have no contact with the outside world, so if we need information that is not available inside the prison I am cut off from that until I leave.

What has been the best takeaway while working on Ear Hustle? How do you see the project evolving?

I have spent the last 25 plus years working as a visual artist- trying to explore ideas through solo work in my studio. Coming together with the men inside San Quentin has been a powerful lesson in the importance of collaboration, negotiation and flexibility. As I said earlier you cannot count on anything inside prison except the fact that most everything is out of one’s control- you always have to be ready to pivot. That leads to very creative problem solving which feeds positively into everything one does in life.

On a deeper more human level I have had the pleasure of getting to know a group of people who some years ago were only caricatures formed in my mind through bad films, TV and shoddy news coverage. I have had many assumptions challenged and have had to re-examine tough issues that I might have breezed by before. I believe it is important for us to live in a place of not knowing, to understand that it isn’t always good to hold on to beliefs too tightly- that to grow, to change, to contribute means to understand that no matter how old we are we should always be in a place of learning.

So I have changed and learned a lot through my time in San Quentin.

One of my former students from the Prison University Project, Ruben Ramirez, took the history of photography class I taught. In that class, we looked at a lot of photography and we used that as a way to discuss life in all its minute detail. We talked about how the camera can transform anything in to something worthy of being seen. At the end of the class he told me he could now see fascination everywhere. Working on the podcast in prison has shown me how we can not only see fascination everywhere but we can also hear it and share it.

As far as Ear Hustle evolving, we have so much going on with it, our plans for the future are to get it played in as many prisons as possible in California and across the United States and the longer-term goal is to figure out how to include more prisons in the actual stories we tell. It isn’t a stretch to want to do that but the challenge is to figure out how.

What else are you working on?

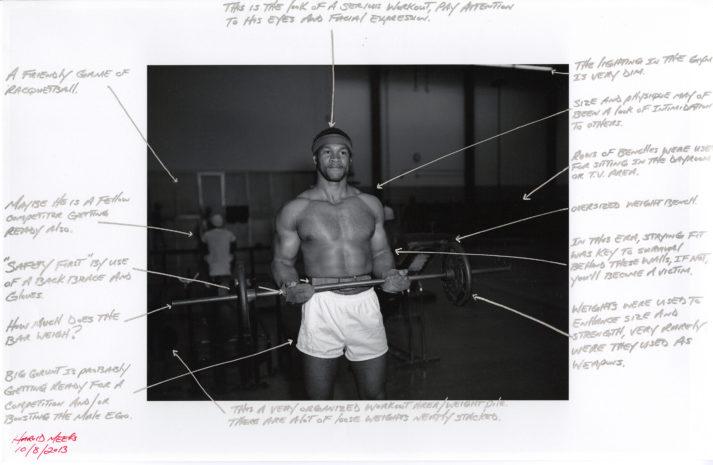

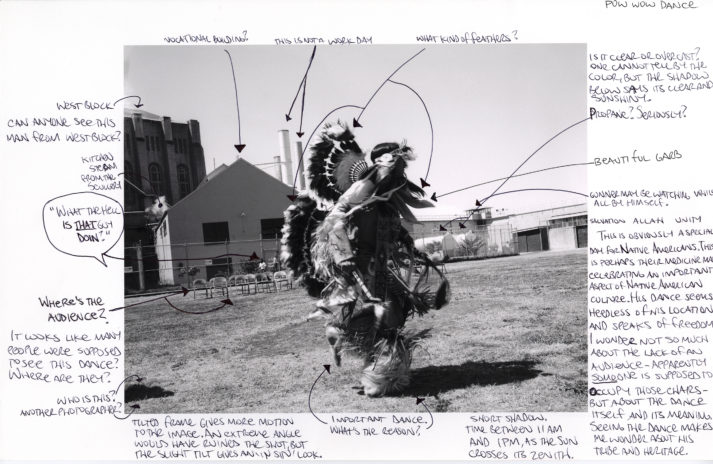

In 2012 I gained access to an unexplored archive of historic negatives taken at and housed inside San Quentin. I am curating this uncharted archive, selecting negatives to print and collaborating with a group of men at the prison to create a new body of work that explores how images can be viewed and interpreted through unique and specific experience.

The archive itself is an exhaustive document of prison life. The 1,000’s of 4×5” negatives were taken between approximately 1950-1987. Many of the images are quite difficult, they were not taken with an artist’s eye or with the intention of creating a visual experience that is generous or transformative. These images were taken by correctional officers whose job was in part, to provide visual proof that an event took place. They are direct, blatant images that rely on the assumption that photography speaks the truth, that it has an unquestionable veracity.

After I print the images some are brought in to the prison and shared with the men. We work together discussing the images and then they take the images and write on them as a way to further explore the image. Each image is treated, in a sense, like a crime scene to be studied, written on and mapped in order to reveal its undisclosed story. The negatives were originally taken to document specific places and events. They were not meant to evoke emotions but through our intervention they become objects that inspire, house memory, personal experience and create a visual dialogue with a mostly invisible population.

I am currently working with Lisa Sutcliffe on an exhibit of this work called The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison. It will open at the Milwaukee Art Museum October 18, 2018 and run through March 10, 2019.

For more information about Nigel, please visit her website and her artist registry page.

Images:

Earlonne Woods & Nigel Poor in San Quentin State Prison Yard, 2017. Photograph by Eddie Herena.

Harold Meeks and Nigel Poor. Gym Profile 7-15-75, 2013. Inkjet print and ink.

Earlonne Woods & Nigel Poor interviewing in San Quentin State Prison Yard, 2017. Photograph by Eddie Herena.

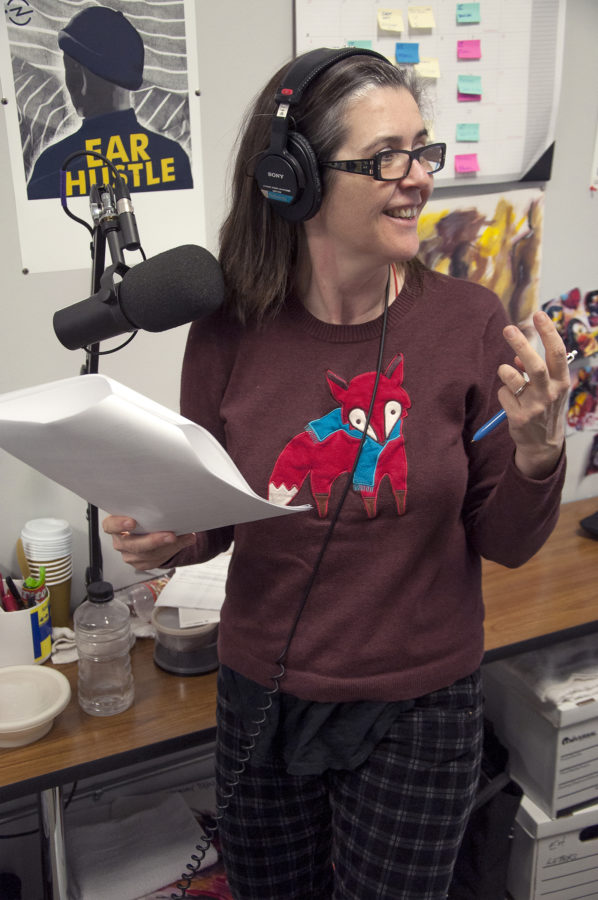

Nigel Poor recording narration for Ear Hustle in the San Quentin State Prison media lab, 2018.

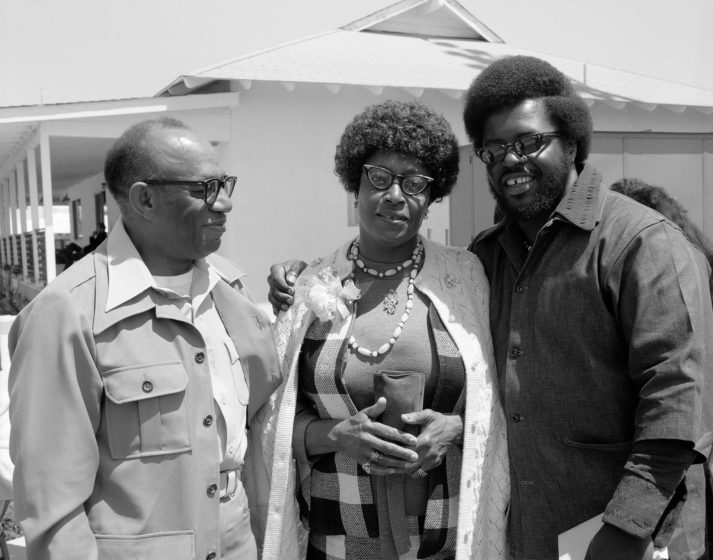

Unknown (American, 20th century). Mother’s Day 5-9-76, from the San Quentin Prison Archive, 1976, printed 2018. Inkjet print.

George “Mesro” Coles-El and Nigel Poor. Indian Pow Wow, 2013. Inkjet print and ink.