Artadia: You received the Chicago Artadia award in 2018. Can you tell us what you applied to the award with and what receiving it was like?

Leonard Suryajaya: I applied with my series “False Idol” and some of my previous work. My previous body of work corresponds with my experience of coming out to my mom and coming out to my home-culture. My bodies of work are always connected to the period of time in my life in which I created it and what I was trying to make sense of. In 2018, I was working on my series “False Idol,” which is about my experience immigrating to America by way of green card. I started the body of work in 2016 and I concluded it at the end of 2019, which was about how long the process of getting a green card was.

Receiving the award was helpful because I used it to submit to the government agency to show I was validated by a nationally renowned organization. I could show I received $10,000 dollars that I had earned. It was a wonderful reminder that I was on the right track.

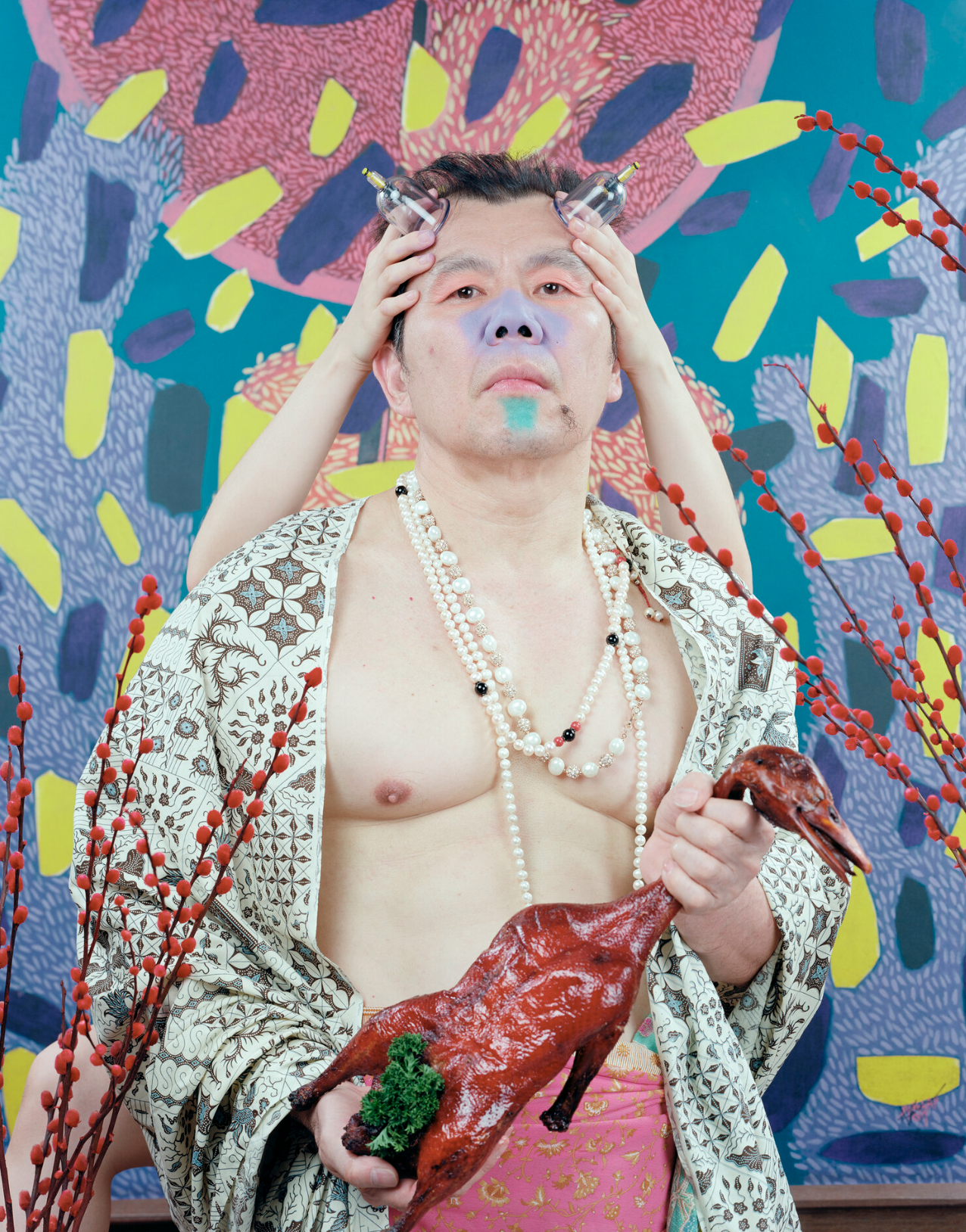

A: Can you talk more about your series “False Idol” and the narrative behind it?

LS: It was quite a monumental body of work in my career because I was a student in America and I didn’t have the security or safety to stay in the country. I got married to my partner maybe 6 months after gay marriage was federally approved, which encouraged me to apply for the green card. The process was very heteronormative and limiting because I was expected to submit and comply with what the American government saw as “worthy.” It was very challenging going through that process being a visual artist, because I don’t have an employer that can vouch for me. I had to prove my worth.

I grew up in Indonesia when anybody of Chinese Descent was not considered a full citizen, and was a persecuted minority. It wasn’t until the year 2000, when there was social reform, that Chinese were respected as full citizens in Indonesia, and by that time I was already 12. There was no way I could trust that the government would look out for me. When I was going through this process with the dreams of making a home for myself in America and processing through all of the traumas and unhelpful conditioning I had received in my early life, I used this body of work to work through those questions and challenges.

A: How important is it to you that the identity, relationships, or people within the image are recognizable elements to the audience?

LS: Early on in my career people have painted the work as “very Asian.” When that was expressed to me it was the time before Black Lives Matter, before anti-Asian violence, when people didn’t have any context for language to speak about diversity. Because I was “different” and “exotic,” it gave them the permission to dismiss me and my work when, in fact, I was trying to open up their ways of thinking. I don’t make work with the objective of explaining everything to people in a box that they could grasp. What I really hope is for people to experience my work through spending time with the layers and meanings and considering how they’re reflected in their own lives.

I don’t expect people to get everything that I went through. People are always [so] hung up on what each part of the image means that they don’t experience my work through emotions or empathy or humanity. If people are just stuck on the “pretty” that’s fine, if people relate to my work in the humor, great. The more that I spend time in my practice, I see that people who understand my background relate to my work and those are the people that make me feel encouraged in making work. The experience of a queer person, an immigrant, a minority or people who have experienced trauma in their life—they can relate to the sense of chaos.