A: Can you tell us about your recent piece, The Rhythm Section?

MO: It’s a piece about music and rhythm. It has to do with jazz, with ancient or more traditional African rhythms, and it also has to do with the often overlooked role that women play in the sustaining of community. It is about how a very mundane exercise like pounding grain becomes a key link in the chain of the community and society. There’s an inherent dignity about that kind of labor. The mechanical pounding sets up a kind of rhythmic, syncopated repetition that speaks to hip hop, jazz, r&b, spirituals and the blues. That rhythm, that drumming – if you will – is the basis of the African diaspora’s engagement and innovation with music.

Although, in a lot of indigenous communities – be they African, be they Native American, be they indigenous to Latin America and the Caribbean – they’re matrilineal communities. So there’s already a historic reverence for the role that women play in the community. But The Rhythm Section is situated in the West, which is historically male-dominated and has diminished the profound contributions women have made to society and continue to make. In our consciousness here in the West, it’s a much more profound statement to make.

A: How do you reckon with the translation of a community based practice into the locale of an art institution?

MO: I think these systems are imperfect. We can only work with the constructs we have, or we can invent a new construct – which then takes time to gain root and credibility in the society in which we live. The best that I can do as an artist is to be inspired by whatever it is and to hopefully – if it’s a cultural practice or has a symbolic meaning as well as a practical meaning for a community – give it dignity through the way that I represent that thing. That speaks about the vitality, the brilliance, the energy, the resiliency of a particular group or culture.

A: How important (or not) is it for your work to be legible? And to who?

MO: When I was younger and in college or graduate school, it was important for me to be much more clear about what the meaning was. I think the first obligation of the artist is to make a thing that’s interesting enough that people want to spend time with it. If the thing, apart from context, apart from the deep meaning of it, doesn’t have a formal dimension to it that draws you in – I think I’ve kind of failed at my obligation as an artist.

Then, it’s about exploring the meanings that the object is imbued with and the multiplicity of those meanings. Some of the work has a very specific cultural context – there are elements of the Black community or of the African diaspora that are an important part of the work. I just went to the Brooklyn Museum and saw the Guadalupe Maravilla show. He’s from Latin America and creates these incredibly beautiful sculptural objects with sound about healing. Just walking in the space, I was really moved by the work. I didn’t know anything about the cultural context, he and I are from two completely different cultural backgrounds, but I could feel the spirit and energy and the quality of the maker’s hand, and that drew me in. And then from there I wanted to explore what the meaning was. What does it mean to put a zipper on an avocado skin? The richness of the quality of the work is universal. That anybody, no matter where they come from can recognize- “there’s something about this thing, I don’t know what it is, I don’t understand it, but I kinda want to spend time here for a minute.” If a person is inclined to explore deeper, then those other meanings may unfold over time. And it may not be in the first viewing, they may have to leave and come back. But if they leave and come back I know I’m doing something right, I’m hitting something within that person that compels them to come back and spend some more time with the work.

"The Rhythm Section," 2022, carved wood, paint and powdered graphite on wood, steel and motors

"The Rhythm Section" (detail and research image), 2022

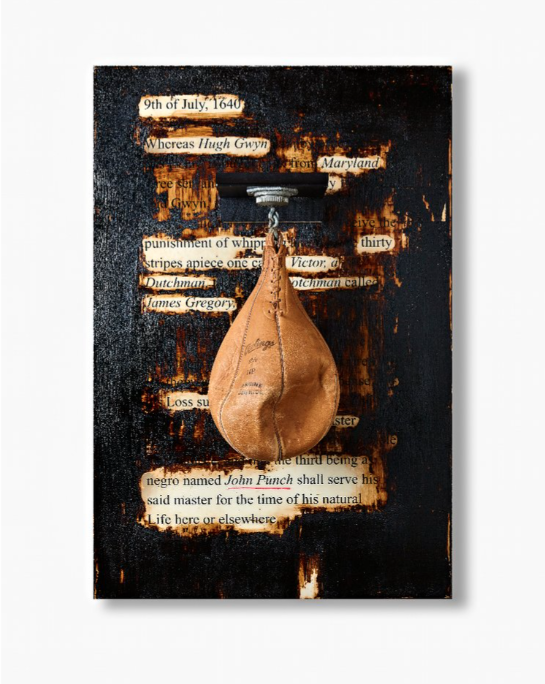

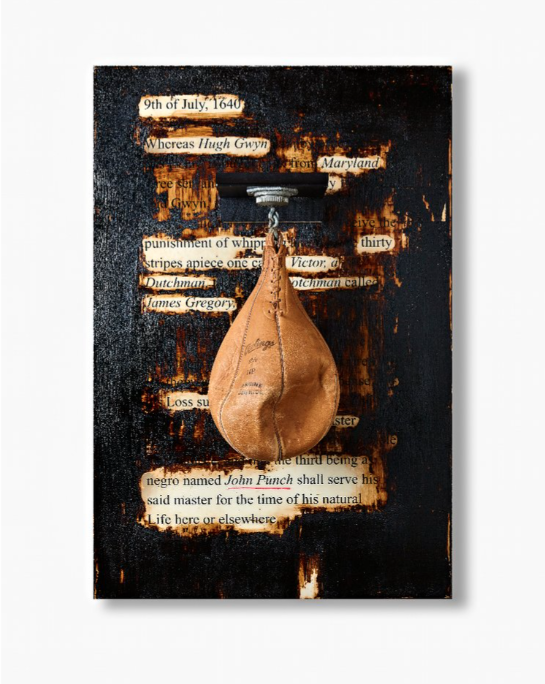

"Punched," 2020, serigraph on wood panel, tar, speed bag and wood

"Root--Anchor," 2016, resin, hair, anchor

"Hive," 2019, carved wood with branches, powdered graphite on wood, bee figurines, paint, serigraph and dye on paper, audio file