Max King Cap earned a master’s degree from the University of Chicago and a doctorate from the University of Southern California. He teaches, curates, and writes about visual art. He lives in Los Angeles. He is a 2001 Chicago Artadia Awardee.

Max joins Artadia for a brief discussion about his work.

You received the Artadia Chicago Award in 2001, just a few years after we were founded. What were you working on at the time? What was driving your work?

I was making sort of object sculptures, installations, performance, video, and some text work. I had already begun the Broadsides series of text works—one was purchased for my college’s presidential residence but because of its subject, the Amadou Diallo murder, it was placed in the basement—Artadia bought one, too. I had always wanted to be an abstract painter but subject matter was too important. I couldn’t simply make marks and shapes on a canvas, no matter how unusual or arresting; it seemed vacuous and cowardly. I was impressed that others could do it so elegantly but for me, there were just too many stories to tell.

You previously lived in Chicago, and now live in Los Angeles. How has each city’s art community shaped you?

Since moving to Los Angeles I have found that architecture and city planning have altered the way I relate to art and artists. That certainly has to do with my lifelong relationship to public transportation. For many years I didn’t own a car, and when I did, it would be ticketed or towed or I would forget where I parked it.

Here in Los Angeles, essentially a two-story city that sprawls across an area greater than the footprint of Paris, one is at the mercy of poor civic planning. Until recently, and just before the advent of Lyft and Uber, the mayor proudly proclaimed that people could legally hail a taxi downtown. It was considered newsworthy. Because of this poor city planning the burden falls on citizens to become clever and tireless logisticians of cultural intake, social cultivation, and vittles accumulation. The city conspires to make all of these things inconvenient, if not downright unpleasant. I see fewer exhibitions a result, fewer concerts, and I have a fairly small patch of the gallery spread where I do most of my viewing and reviewing.

As an artist who is often focused on political themes, your work (and politics itself) has obviously evolved since 2001. What surprised you most as your artist statement developed with the times?

An ever-increasing cynicism. Not only about the planet, my country, and the world in general but about art itself. I suppose I lost faith in art for a while and have never fully recovered. There was a time when art could make me cry, that I would experience a sort of rapture (no fainting) at seeing a work in a museum. I would visit the Art Institute in Chicago to see a single work, stay in contemplation of it for twenty minutes, and leave elated. Not now. I’m a sort of art agnostic. However, after teaching in art departments and having exhibitions for more than 20 years, I see little opportunity for a career change. This is what I am stuck with; it has become rather like a factory job, but without a lunch-pail. Or union wages.

You have been working on the series Broadsides since 1995. When you began, did you see yourself adding to this collection more than twenty years later? What have you learned from such a long-term project? Do you ever see yourself calling it complete?

When Scarecrow, a broadside on the murder of Matthew Shepard, came to mind I was struggling to understand not the murder itself (murder is sadly commonplace) but the personal brutality of the event. It was staged like an act of theatre, as if the two murderers were watching themselves and improvising as they went along moving toward some spectacular climax. They knew that they were doing something that would alter there lives—they previously had a history, afterward they would have a future, and the murder would the irrevocable turning point. I also knew this horror would be a marker in my personal history. We all have them, a “Where were you when…?” answer that locates us in time, returns us to that moment in our lives. I was at the firehouse (I was a firefighter then) when the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded; the news of Matt Shepard reached me in a Los Angeles pancake house when I was visiting my future spouse. My life, and I expect the lives of many others, are similarly punctuated. The Broadsides will continue as long as events continue to choose the headings of my chapters.

You have a new series of paintings based on the uniforms worn by black baseball players in segregated leagues. How did this idea develop? What drove to you paint the uniforms in particular?

The paintings grow from my fondness for the game itself and the fallibility of memory, both individual and national. I grew up watching the Cubs. One of my first memories was one of their freakish, late season collapses—all the adults were complaining but I didn’t understand. In later years I did, though, and I repeated their frustration. By the time I was old enough to go to a baseball game by myself I learned that retired Cubs hero Ernie Banks, the first African American player on the team, he had previously played in the Negro Leagues. I hadn’t even known there was such a thing as segregated baseball! That such a social configuration could have been standard practice seemed metaphysical. How could such a bizarre logic have been believed? And for so long. But I was a little boy then. White police officers were kind to me. I was not a threat. Not yet. Then puberty hit. The uniforms of Negro Leagues baseball players were indicators of practice in a certain acceptable realm of endeavor, like that of a Pullman porter. Stepping out of that realm, of course, was strictly forbidden. There are now fewer Black ballplayers on the field; the percentage is near the 1958 level. Why? Some of the reasons are the same as the wider societal ills of African Americans—red-lining, loss of union jobs, substandard schools, and a judicial system that criminalizes Blackness. The paintings, square like bases, are akin to those Blue Plaques that can be seen on British buildings. They usually say that somebody special did something terrific here. Black baseball is like that. A sort of faded, glorious memory.

Currently, you do a lot of writing on art and artists. How has your own background as an artist influenced the way you evaluate other artists’ work? What do you find most challenging in writing about art? What do you love about writing on art?

I began as a theatre student (I won a Creative Capital grant for an installation/ operetta). My change of majors was capricious. I write because it is something that I do well, fairly effortlessly—I suppose that is why I abandoned it; I didn’t respect my skill— and with less doubt than art making. Since I have worked in a variety of media I find writing about the artwork of others an enjoyable way to gather together a variety of historical and cultural associations to leaven the visual artworks with an influence and interrelation that is greater that what can often be reckoned from their appearance alone. I have started writing again. I’ll have a play excerpt in a small literary journal soon, and I’m fattening and thinning my dissertation to pitch to publishers. We’ll see what happens.

To see more of Max’s work, visit his website and artist registry page.

Images:

Harrisburg Giants, from NLB. Oil on panel, 15″x15″, 2018

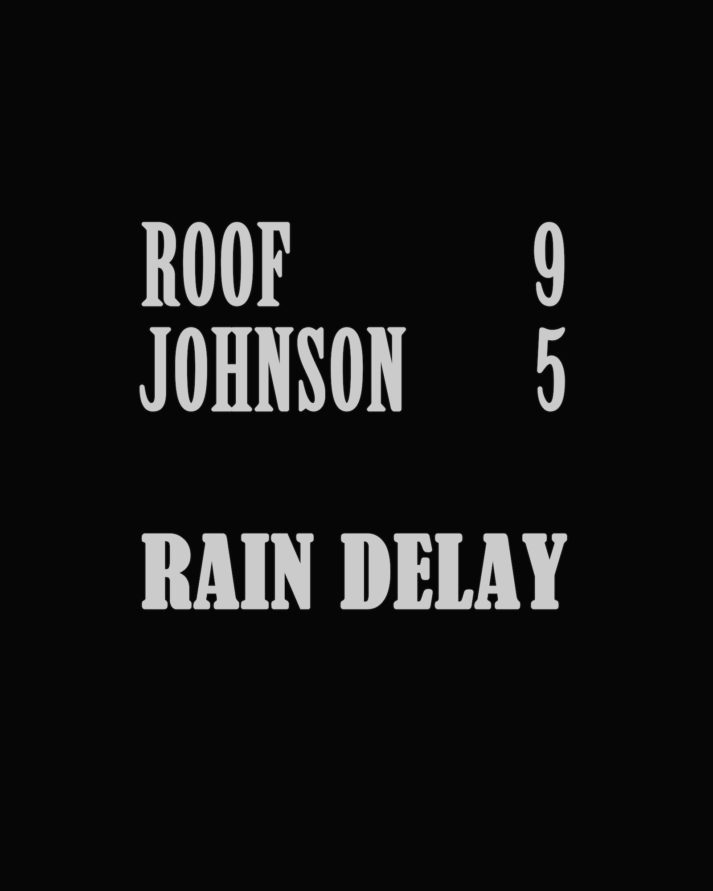

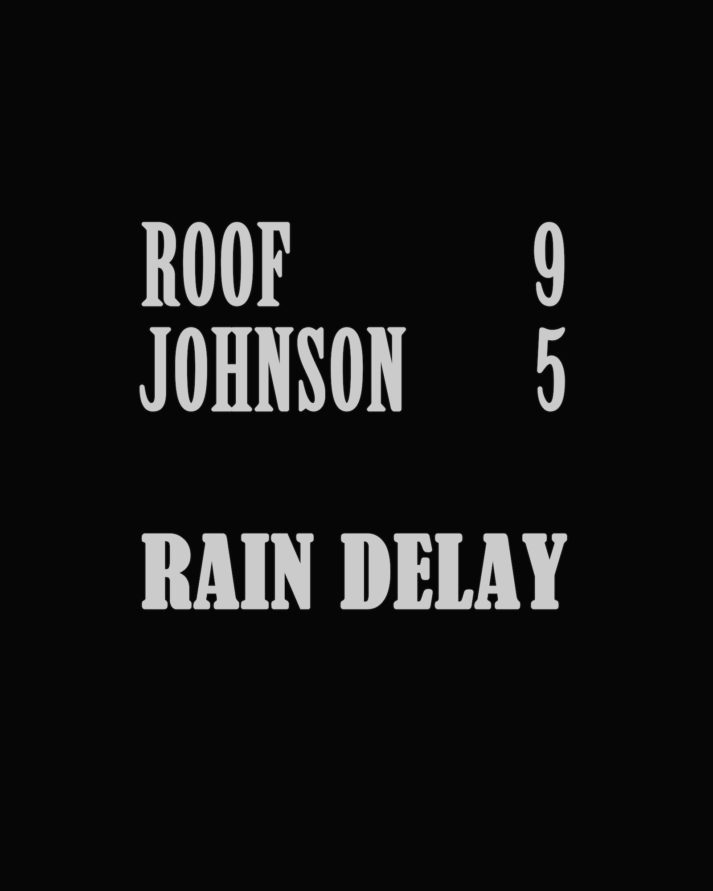

Rain Delay, from Broadsides. Digital Print, Variable, 2016

Scarecrow, from Broadsides. Digital Print, Variable, 2000

American Giant V, from NLB. Oil on panel, 24″x24″, 2018

Black Baron I, from NLB. Oil on panel, 15″ x 15″, 2018