A: Can you speak about the process behind your “Maxiatures” series in its use of both photography and collage?

SS: I feel like I’m a storyteller. I stage stories that I create. When I did collages with photoshop, it opened up a whole new world for me – I could be more imaginative. The miniature has so many stories within it that I could create. It takes me a long time, but I really love it.

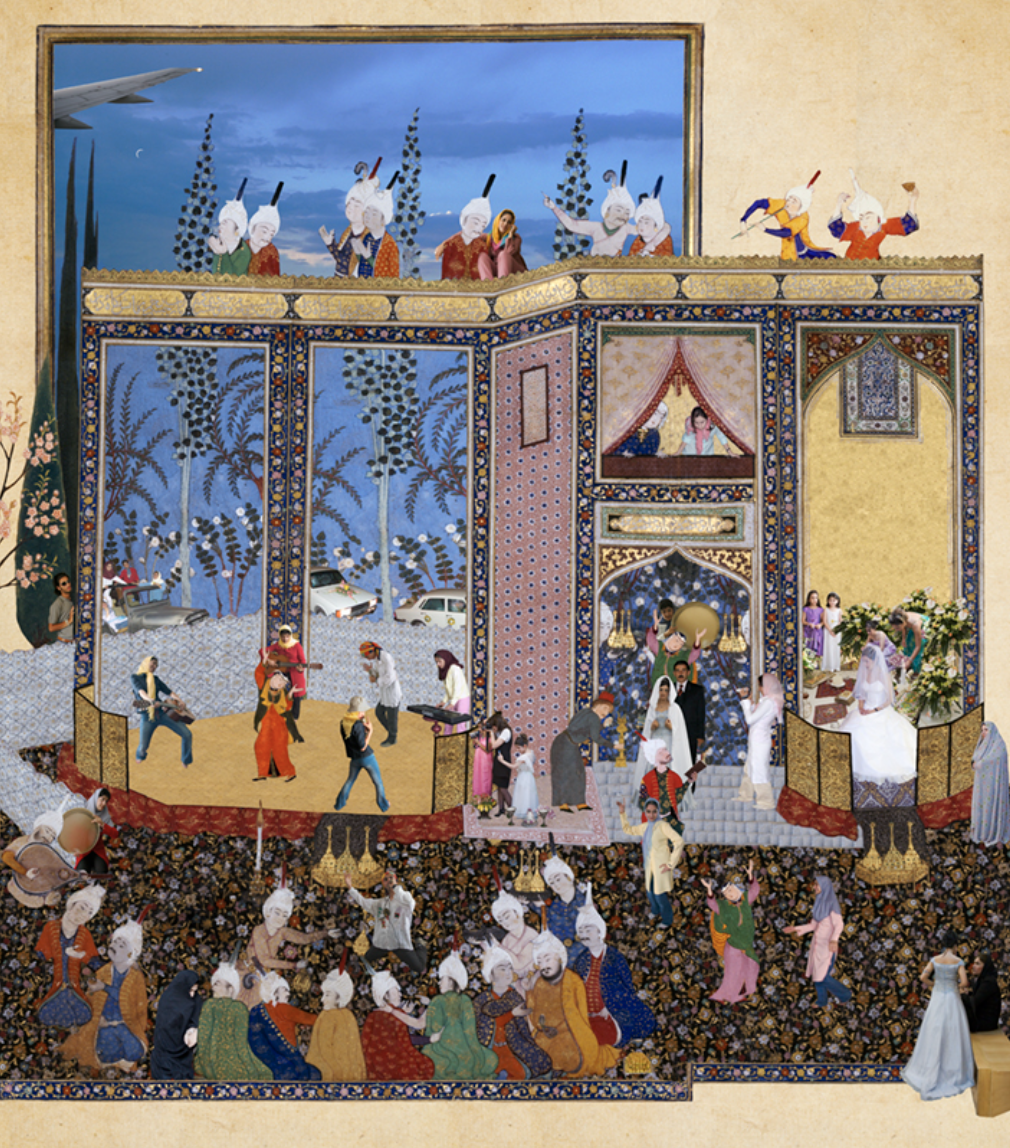

I collect Persian miniatures, scan them, put in my own images and landscapes, change them and enlarge them. That’s where the idea of “maxiature” comes from – maximizing what we used to see only in 7 x 10 images. Now digitally we have a choice of looking at all the details and appreciating it. I feel like I’m collaborating with the artists working in the 15th and 16th centuries.

A: How are your photographs chosen to accompany the illustrations within the Persian miniatures?

SS: Persian miniatures usually depict the life of the court people. When I looked at these images, I saw these Persian figures interacting together and I imagined what it would look like if this was happening in the 21st century on the streets of Iran. Since I had documented a lot of landscapes and images of younger women and men in their environments, I could look at the miniature and create my own story of what is really happening culturally in Iran.

A: What draws you to a certain Persian Miniature for an artwork?

SS: Sometimes it’s about covering like in “frolicking woman in the pool.” I noticed I had gone to many places – especially beaches – where women are covered, but men are not. When I looked at the original miniature, I saw these naked women depicted in the pool. The men are in their bathing suits but the women are covered.

“The feast of Id” is about how many young people can not afford to pay for their wedding in Iran. The government started to use a whole place for six or seven weddings to happen at the same time. And then I used the women again as performers, although they’re covered. I want people to question these cultural things. This is how I choose many of my images.

A: “Persian Delights” is a series of collages that are pared down in comparison to “Maxiatures.” How do you find this act of simplifying to affect the viewing of the work?

SS: I feel like “Persian Delights” is more talking about an Iranian who is living in the West. I use a focused image because I want to show how we westerners stereotype the Middle East and the Middle East has a completely different image of us. If you look at “Kite Runner,” for example, it has flags, one with voluptuous women in bikinis, the American flag, Mickey Mouse. I wanted to show how I feel as an Iranian American living in the West, as we Americans think of Iranians as very religious, always reading the Quran, and not really having a life.

"Movie Set," 2007, Archival Inkjet print, Edition of 3.

"Frolicking Women in the Pool," 2007, Archival Inkjet print, Edition of 3.

"The Feast of Id," 2010, Archival Inkjet print, Edition of 6.

"Kite Runner," 2007, Archival Inkjet Print, Edition of 6.